The Chinese Hexagrams

The DNA nucleotide were first deciphered by the Chinese. Around the year 1050 BCE, tradition states that Emperor Wen, founder of the Zhou dynasty, created hexagrams. He did this by doubling the trigrams. These hexagrams are six-lined figures. He numbered and arranged all of the possible combinations. There are 64, and he gave them names.

They did this in the manner that they interpret life. As my followers know, this discovery was turned into the IChing hexagrams thousands of years before 1961. The Chinese created 64 hexagrams that stood for Life first. They accomplished this long before Western white men worked in the lab in white coats during the 60’s. Western scientists took these hexagrams and ascribed triplet letters to them. Two lines of the hexagram represented one letter: A, C, G, T, or U for the RNA. Before the scientists did that, Leibniz turned the hexagrams into binary code or 0’s and 1’s.

So the time spiral goes; The Chinese made significant contributions first by designing and giving meaning to the Hexagrams. The production of stelae by the Maya had its origin around 400 BC and continued through to the end of the Classic Period, around 900, although some monuments were reused in the Postclassic (c. 900–1521).Then Leibniz developed his binary code by looking at the Chinese symbols as lines and dashes or 0 and 1. Next was the Turing machine, hypothetical computing device introduced in 1936 by the English mathematician and logician Alan M. Turing. This was the predecessor of the computer which added the electronic element to the interpretation of our DNA. Then Rosalind Franklin photographed the DNA double helix, but her work was unacknowledged. Then Watson and Crick introduced their DNA model in 1953. Rosalind Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling had photographed it in 1952. But Watson and Crick got all the credit. Now we arrive at Marshall Nirenberg and his colleagues in the 60’s in this article. They were at the National Institutes of Health and interpreted the language of the genetic code.

Before you read his, know this. The Maya, the Chinese, and Rosalind Franklin gave the world the genetic code in its original intended form. It has since been obfuscated by white coat men in the labs of universities and at the National level. I hope to bring it back around to its original, expanded meaning, lost since the Maya. Such is the nature of Oracles in a technologically dominated world.

The link to this article.

https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/geneticcode.html

National Historic Chemical Landmark

Dedicated November 12, 2009, at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

DNA consists of a code language comprising four letters. These letters make up what are known as codons, or words. Each codon is three letters long. Marshall Nirenberg and his colleagues at the National Institutes of Health interpreted the language of the genetic code. It was their collaborative work that achieved this. Their careful work, conducted in the 1960s, paved the way for interpreting the sequences of the entire human genome.

Contents

- Modern Genetics: A Monk and a Double Helix

- Marshall Nirenberg’s Early Career

- Experiments with Synthetic RNA

- Breaking the Genetic Code: The “poly-U” Experiment

- The Nobel Prize and Reactions

Modern Genetics: A Monk and a Double Helix

Modern genetics begins with an obscure Augustinian monk studying the inheritance of various traits in pea plants. Gregor Mendel’s laws of inheritance revealed the probabilities of dominant and recessive traits being passed from generation to generation. Mendel’s research received little recognition in his lifetime. The significance of Mendel’s laws was recognized only in the early 20th century.

With that rediscovery came interest in how genetic information is transmitted. Oswald Avery, a bacteriologist at New York’s Rockefeller Institute, demonstrated that deoxyribonucleic acid, DNA, produced inheritable changes. This discovery was not well received. How could DNA store genetic information? It was a substance containing only four different nucleotide building blocks. Others discovered that DNA varies from species to species. Then, in 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick at Cambridge University amazed the scientific world. They introduced their model of DNA, known as the double helix. Watson and Crick recognized that the double strand might allow replication.

How could DNA, a double helix made up of only four different nucleotide, determine the composition of enzymes (proteins)? These enzymes are long peptide chains composed of twenty different amino acids. The race to discover the genetic code which translates DNA’s information into proteins was underway. To stimulate the chase, George Gamow, a theoretical physicist, organized the twenty-member “RNA Tie Club.” Each member wore a tie with the symbol for one of the 20 amino acids. The members shared ideas on how DNA transmitted information.

The scientist who won the race was not a member of the “club.”

The “Deciphering the Genetic Code” is a commemorative booklet. It was produced by the National Historic Chemical Landmarks program of the American Chemical Society. The booklet was published in 2009 (PDF).

I thought if I’m going to work this hard, I might just as well have fun. By fun, I mean I wanted to explore an important problem. I wanted to discover things.”

— Interview with Marshall Nirenberg, July 15, 2009.

Marshall Nirenberg’s Early Career

Marshall Nirenberg earned a Ph.D. in biological chemistry. He studied at the University of Michigan. His dissertation focused on the mechanism of sugar uptake in tumor cells. He continued that research as a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health. In 1959, he joined the staff of NIH as a research biochemist.

Nirenberg gave some thought to what he wanted to study as an independent investigator. He said in 2009, “At that time, the mechanism of protein synthesis was very incompletely known.” Messenger RNA had not been discovered.

Nirenberg’s initial goal was to find out if DNA or RNA, copied from DNA, was the template for protein synthesis. Nirenberg had no formal training in molecular genetics. He knew that this was an incredibly risky project. When you take your first position, you want to hit the deck running. You want to show you are a productive scientist. Nirenberg had no experience in the field. He had no staff at the outset and was in a race against the best scientists. He knew he “could fail easily.”

*This and subsequent quotations, unless the text indicates differently, are from an interview by Judah Ginsberg and Marshall Nirenberg, conducted in his laboratory on the campus of NIH on July 15, 2009.

Experiments with Synthetic RNA

Nirenberg and Heinrich Matthaei started their experiments by studying DNA and RNA. Matthaei, a postdoctoral fellow from Germany, collaborated on the research. In DNA, the nucleotide are adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C) and thymine (T); in RNA, uracil (U), replaces thymine.

They chose a cell-free environment, created when cell walls are broken down, releasing the cell’s contents. The remaining cytoplasm can still synthesize protein when RNA is added. This allows the researchers to design experiments. They can determine how RNA works free of the complicated biological processes that could shroud molecular activity.

Nirenberg and Matthaei selected E. coli bacteria cells as their source of cytoplasm. They added the E. coli extract to 20 test tubes, each containing a mixture of all 20 amino acids. In each test tube one amino acid was radioactively tagged, a different one in each test tube. The reaction could be followed by monitoring radioactivity: incorporation of a “hot” amino acid would form a “hot” protein.

Breaking the Genetic Code: The “poly-U” Experiment

At 3:00 in the morning on May 27, 1961, Matthaei begins his experiment. (Yellow 13 Seed which hits in 3 days) He adds synthetic RNA. It was a Saturday. The RNA is made only of uracil units. He adds it to each of the 20 test tubes. He finds unusual activity in one of the tubes. This tube contains Phenylalanine. The test results are spectacular. A chain of uracil units in the “hot” tube directs the addition of the “hot” amino acid.

Nirenberg and Matthaei understood what had happened. Synthetic RNA made of a chain of multiple units of uracil gave instructions. It directed a chain of amino acids to add Phenylalanine. The uracil chain (poly-U) served as a messenger directing protein synthesis. The question of how many units of U were required was yet unanswered. However, the experiment proved that messenger RNA transcribes genetic information. It transcribes this information from DNA. It directs the assembly of amino acids into complex proteins. The key to breaking the genetic code—molecular biology’s Rosetta Stone—had been discovered.

Nirenberg presented his successful poly-U experiment at an international biochemistry congress held in Moscow in August, a few months later. He was acutely aware of his outsider status. He said, “I didn’t know the people in molecular biology. I didn’t know anybody in protein synthesis. I was working on my own.” That may explain why only 35 people attended his talk and why the audience “was absolutely dead.”

Nirenberg experienced a serendipitous event that changed everything. He had met Watson the day before. Nirenberg told the co-discoverer of the double helix about his results. Watson was skeptical about Nirenberg’s claims. However, he convinced a colleague to attend the paper. The colleague reported that Nirenberg’s findings were real. Watson then told Crick, who arranged for Nirenberg to present his paper again. This time, it was in a major symposium on nucleic acids at the same congress. “The reaction was incredible,” Nirenberg remembered. “When it was over, the audience gave a standing ovation. I didn’t know it at that moment. For the next five years, I became like a scientific rock star.”

Marshall Nirenberg performing an experiment, circa 1962.

Courtesy the National Institutes of Health.

Nirenberg and Matthaei “cracked” the first “word” of the genetic code. Afterward, scientists raced to translate the unique code words for each amino acid. They hoped to someday read the entire genetic code of living organisms. Nirenberg assembled a team of about twenty researchers and technicians.

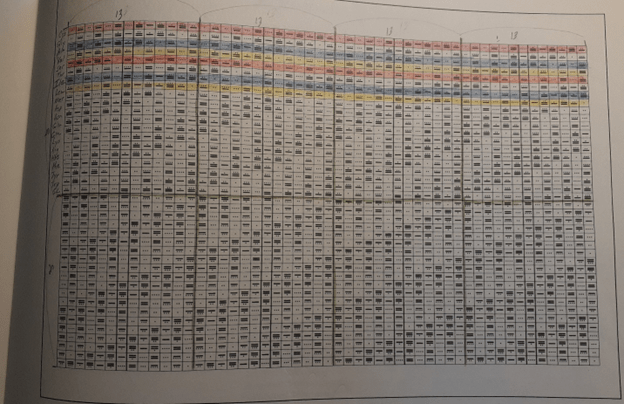

Nirenberg and his colleagues used the poly-U experiment as a model. They identified nucleotide combinations for the incorporation of other amino acids. The researchers found that the coding units for amino acids contain three nucleotide (a triplet). They combined four nucleotide in three-letter codes. This combination yielded 64 possible combinations (4 x 4 x 4). This was sufficient to describe 20 amino acids.

They discovered the codes for other amino acids: for example, AAA for Lysine and CCC for Proline. Replacing one unit of a triplet code with another nucleotide yielded a different amino acid. For instance, synthetic RNA containing one unit of guanine and two of uracil (code word: GUU) caused incorporation of Valine.

In 1964 Nirenberg and Philip Leder discovered a method. Leder was a postdoctoral fellow at NIH. They determined the sequence of the letters in each triplet word for amino acids. By 1966 Nirenberg had deciphered the 64 RNA three-letter code words (codons) for all 20 amino acids. The language of DNA was now understood and the code could be expressed in a chart.

The Nobel Prize and Reactions

In 1968 Nirenberg won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his seminal work on the genetic code. He shared the award with Har Gobind Khorana (University of Wisconsin). Khorana mastered the synthesis of nucleic acids. Robert Holley (Cornell University) also shared the award. Holley discovered the chemical structure of transfer-RNA. Collectively, the three were recognized “for their interpretation of the genetic code and its function in protein synthesis.”

Nirenberg describes the ceremonies surrounding the Nobel as “a week of parties.” Not quite all parties, however, since the rules of the Nobel require recipients to write a review article. This proved a challenge for Nirenberg, who had turned his research attention to neurobiology. ”I found it very difficult,” he later admitted, “to break off from neurobiology and go back to nucleic acids.”

As a Nobel Laureate, Nirenberg received many university offers that included higher salary, more laboratory space, and larger staff. He turned them all down, preferring to spend the rest of his career at NIH. “The reason I stayed,” he says, “was because the thing I had least of was time. I figured that if I went to a university, I would use a third of my time to write grants. I believed I could use that time more productively by doing experiments.”

In 1961 The New York Times, echoing President Kennedy, reported about Nirenberg’s research. It showed that biology “has reached a new frontier.” One journalist suggested the biggest news story of the year was not Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin orbiting the earth. Instead, the biggest story was the cracking of the genetic code.

Deciphering the genetic code raised ethical concerns about the potential for genetic engineering. Nirenberg addressed these concerns in a famous editorial in Science in August 1967. He noted “that man may be able to program his own cells.” This could happen before “he has sufficient wisdom to use this knowledge for the benefit of mankind.” He emphasized that “decisions concerning the application of this knowledge must be made by society.” Only an informed society can make such decisions wisely. When asked several decades later if society has acted “wisely” regarding genetic engineering, Nirenberg answered, “Absolutely!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.